NOW AVAILABLE ONLINE AND BY REQUEST AT YOUR LOCAL BOOKSTORE

— Click here to buy the book online —

PHARMAGEDDON: A Nation Betrayed

PHARMAGEDDON: A Nation Betrayed

A National Trial Lawyer Reveals an Industry Spinning Out of Control

by Stephen A. Sheller, Esq.

with New York Times best-selling author Sidney D. Kirkpatrick

Chapter 1

Bush v. Gore: How the Fox Got in the Hen House

How a “Stolen” Presidential Election Contributed to Historical Pharmaceutical Industry Fraud

In my nearly five decades practicing law, I have litigated some of our nation’s most loathsome betrayals of public trust: from birth defects caused by a drug purportedly designed to help pregnant women, deadly diet pills, FDA-approved vaccines that are actually poisonous, and legislative and judicially-created preemption laws protecting corporate criminals from prosecution and responsibility. But it was voter fraud litigation I filed in the 2000 presidential election that gave me an insider’s look at what has turned out to be the greatest betrayal of all. Had voting rights protections in Florida been enforced and justice served in our Supreme Court, there might never have been an Iraq War, the mortgage crisis melt-down, our trillion-dollar deficit, a polarized and ineffective Congress, or a pharmaceutical industry that today operates like a crime syndicate.

I understand the skepticism you may have in my making such a bold pronouncement. Hindsight, as they say, can take you only so far. But please indulge me while I explain the voter fraud that took place in Florida in 2000 and how this travesty of justice left a fox guarding our executive henhouse. Though you may not agree with the conclusions I have drawn, you will gain an insight into how I practice law and, in the chapters ahead, understand the many reasons I feel compelled to try and rein in a pharmaceutical industry that’s out of control. It’s not that I’m less offended by other corporate misdeeds, injustices, and influence peddling. Rather, I believe it’s my calling to serve children, the infirm, and the elderly—those whom the pharmaceutical industry invariably chooses to exploit and who, like Gabriel Meyers, most often fall through the cracks when our nation fails.

WATCH: Sheller on Butterfly Ballots and His Mother in Law

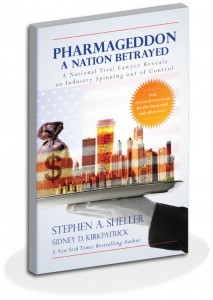

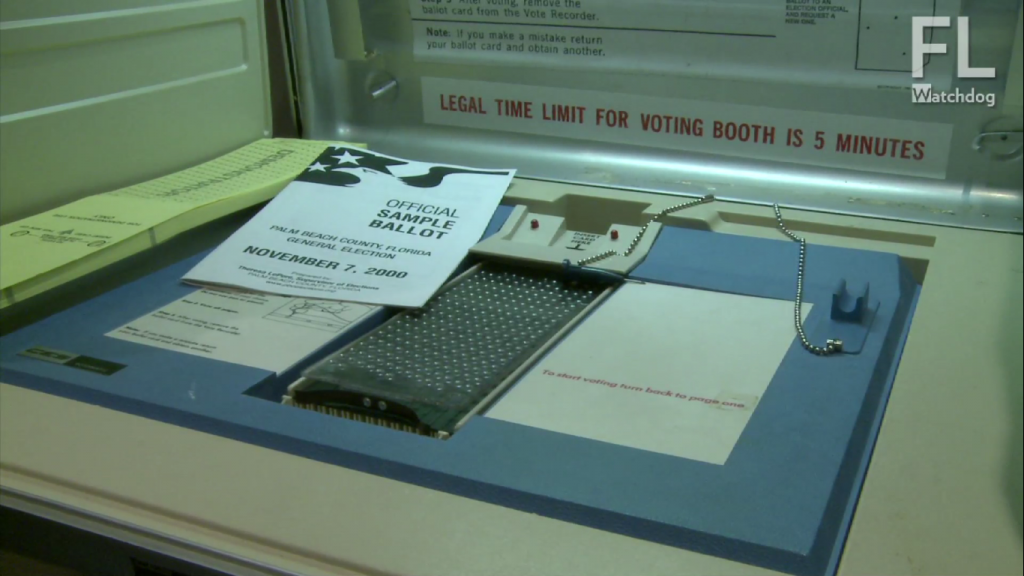

Like so many of my cases that start out as issues affecting my friends, my family, and our coworkers and gradually spread into the larger community, my voter fraud investigation was triggered by a telephone call, in this case from my mother-in-law, Bobbie Mitnik, in Palm Beach County. She phoned my office in Philadelphia on Election Day afternoon, November 7, 2000, to express her deep concern. She had entered her polling place intending to vote Democrat but found the ballot on the punch card vote recorder at her polling station to be so confusing that she couldn’t be certain if she had voted for Democrat Al Gore or ultra-conservative Reform Party candidate Pat Buchanan. Not only that, but according to her, the pre-election instruction booklet she received in the mail, which contained the sample ballot she had filled out at home, was laid out differently than the one displayed on her Votomatic vote recorder in the polling booth.

Upset, Bobbie asked me what could be done. After calming her down and promising that I would look into it, I phoned friends and other family in Palm Beach and discovered that her experience that Tuesday was not unique. Other elderly Floridians in that county had encountered the same problem. The infamous “butterfly ballot,” as it was later known, hadn’t listed the three presidential candidates’ names one atop the other on a single page as had been done elsewhere in Florida but, instead, had put Gore’s and Buchanan’s names on different pages opposite one another, making it difficult for the voter to know where they should punch the card for the candidate of their choice. Al Gore’s was the second name on the first page of the ballot, just beneath George W. Bush, but to vote for Gore, one had to punch the third hole in a line down the middle of the two pages. Voters were punching the second hole on the left thinking it was for Gore, but the vote was cast for Buchanan, whose name was listed first on the second page.

The informal phone queries I conducted from Philadelphia revealed what the press would announce the next morning: like my mother-in-law, hundreds and perhaps thousands of voters were confused. Complaints to the Palm Beach election supervisors were so numerous that the telephone lines were jammed the entire day of the election. Moreover, I had only to compare the tabulated vote favoring Bush with the exit polls returns favoring Gore to see a glaring inconsistency. Something wasn’t right in sunny Palm Beach.

I can be accused of many things, but sitting on my hands is not one of them. First on my agenda was calling my friend Ed Rendell, the former Philadelphia mayor, future governor of Pennsylvania, and at that time the chair of the Democratic National Committee. Rendell agreed I should “get down there, figure it out, and see what could be done.” On my own dime, of course.

Click here for Book Facebook Page

Forty-eight hours later, Florida friends and colleagues Dave Krathen and Gary Farmer joined me at the Palm Beach County Courthouse to file a class action suit seeking to enjoin the certification of the Palm Beach County vote by Katherine Harris, the Republican Secretary of State. We couldn’t have imagined that what began with my mother-in-law’s telephone call would mushroom into multiple state and federal complaints that would ultimately result in a post election battle in the US Supreme Court. But that’s the exciting thing about what I do and what I believe all of us must do to protect our rights as citizens: voice a complaint. We don’t have to see the larger picture to set the wheels in motion. Merely taking the first step will often trigger events well beyond our imagination.

WATCH: Election 2000: Sheller on CNN with Greta Van Susteren

Most of those forty-eight hours leading up to our Palm Beach filing were spent in transit, racing from one place to another, collecting ballots and other documentary materials, gathering voters’ affidavits, and assembling the help we needed to draft the complaint. To our delight, Judge Kathleen Kroll granted our restraining order that Thursday afternoon and scheduled a formal hearing before Judge Lucy Chernow Brown to take place five days later on Tuesday, November 14, at 1:00 p.m.

I alerted Ed Rendell of our filing and requested as much legal help and assistance as he could provide. He embraced our efforts, as neither the Al Gore campaign nor the Democratic Party had yet mobilized to challenge the election. Rendell put me in touch with campaign volunteers and fellow Philadelphia attorneys who were familiar with post-election litigation. The result was Rogers and Kaplan v. Palm Beach Canvassing Commission.

As it turned out, we were in an important position at the head of a long line of other soon-to-be-filed litigation challenging the Palm Beach vote. In addition to the controversial ballot layout, which had possibly been designed to mislead voters into casting their ballots for candidates not of their choosing, serious other questions were being raised. Many thousands of votes hadn’t been counted because the pointer or stylus used in the Votomatic punch-card machine hadn’t cleanly penetrated the ballot. If a hole in the ballot card was not cleanly punched through, leaving the much-discussed “hanging” or “dimpled chads,” the tabulating machines didn’t count the vote. The problem was that Votomatic machines in black-majority precincts were three times more likely to leave hanging or dimpled chats than in nonblack precincts. Had inferior Votomatic machines been installed in precincts where the Democratic vote was expected to be higher than the Republican vote?

Another controversial subject that Gary and I would bring to public attention was the paper stock the ballots were printed on. The stock delivered to the various poling sites was not uniform throughout the state. The thicker the paper stock, the more likely it was that the stylus wouldn’t punch a hole cleanly through it. As the Florida ballots were manufactured in the Dallas suburb of Addison, Texas, the home state of Republican candidate George W. Bush, you have to wonder. Were poor-quality punch cards sent to polling stations where Gore was expected to do well and higher-quality punch cards sent elsewhere?

These and so many other issues would require us to conduct extensive research. In the meantime, however, in preparation for our November 14 hearing, we wrote bench memos on the relevant legal issues, most particularly why the butterfly ballot did not meet the requirements of Florida’s election code. To buttress our case, we called expert statisticians who would present the court with data that conclusively showed that the Palm Beach County ballot’s layout resulted in two thousand or more votes intended for Al Gore that were instead cast for Pat Buchanan. This was, incidentally, just what Buchanan was telling the media. He too had been astonished by the number of votes for him in Palm Beach, a county where he had not campaigned and had virtually no support. A vote for him, Buchanan readily admitted, reflected votes intended for Gore. Miscast votes, however, were not the only problem. As the Miami Herald would later confirm, voters in Palm Beach County were one hundred times more likely than elsewhere in South Florida to invalidate their ballots by voting for both Gore and Buchanan.

Theresa LaPore, the Palm Beach election supervisor who approved and helped to design the butterfly ballot, was helpful to our cause. Before her abrupt refusal to publicly discuss the matter, she granted an interview to local media acknowledging that the ballot design had been laid out substantively differently than in other counties. Her intention, she said, was to increase the font size on the ballot card, so it could be read more easily by the elderly residents of Palm Beach, but the effect turned out to be confusing. “Madame Butterfly,” as LaPore came to be known, regretted her candid remarks, as they confirmed our underlying belief that Palm Beach voters were treated differently than in other counties and in the country at large.

Further suspicion was cast on the ballot design when an investigation revealed that a similar design by LaPore’s predecessor had been equally problematic. As the Palm Beach Post would report, a butterfly ballot four years earlier had caused an estimated fourteen thousand votes intended for Republican Bob Dole to be dismissed for double punching. Dole was the second name on the 1996 ballot, just as Al Gore was in 2000. Rather than redesigning the ballot and replacing the equipment, the same machines and ballot type had been used again. More significantly, this information had been concealed from voters in 1996 and was again in 2000.

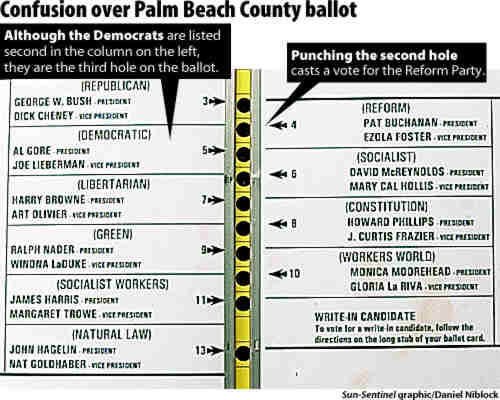

Later revelations would cast even more doubt on the reliability of the voting machines. The ones used in Palm Beach were not authentic Votomatics but antiquated, imitation, or “clone,” Votomatics produced by the Data-Punch Corporation in Illinois. As the Miami Herald would report, LaPore’s twenty-year-old machines were peppered with worn-out, outdated, and ineffective parts, which included inflexible and cracked plastic springs, battered templates, and worn rubber T -strips. Herald reporter David Kidwell, aware of the machine’s faults, visited the warehouse where they were stored and ran his own tests on them. His test ballots showed a significant number of dimpled chads, imperfections that would be rejected by computer scanners when counting votes.

If this were not reason enough to demand a recount, in predominantly black and Democratic Duval County, a dot mysteriously showed up on computer scanning machines, causing the counting device to see it as a vote. When the dot was coupled with a vote for another candidate, which was almost always Gore, the machine saw two votes and counted neither, leading to a loss of about three thousand votes for Gore. Over- or undercounting also took place in districts that used ballots on which the voter filled in the oblong area next to the chosen candidate with a provided pencil, but, in these instances, the voter’s intent was usually clear.

Allegations of fraud and misconduct continued unabated. As the Miami Herald reported, LaPore’s poll workers had learned of serious mechanical problems even before the polls opened but had done nothing to correct them. By state law, poll workers are required to confirm the accuracy of ballot books on all machines immediately before precincts open. This includes testing all machines. The machines in Palm Beach County and some in Miami-Dade County failed those mechanical tests but remained in service anyway. There was, as our statistical analysis showed, an incontrovertible correlation between these faulty tests conducted by poll workers before 7:00 a.m. and the precincts that reported high numbers of rejected votes later in the day.

Had a criminally inclined element in Florida learned from the mistakes made four years earlier and used them to their advantage in the 2000 election? I didn’t yet know the full extent of the behind-the-scenes decisions that contributed to the faulty Palm Beach vote, but I suspected that we were onto something.

What we were up against became clear the day before our court appearance, when Dave Krathen and I met in Gary Farmer’s office in Fort Lauderdale and were dismayed to discover that Bush campaign attorneys had filed a half-dozen motions to stop our having the hearing before the specifics of our case became known. To my consternation, Bush’s people had hired the Greenberg Traurig law firm based in Miami, a formidable foe with hundreds of attorneys on staff. Incidentally, the firm’s founding partner and CEO was Larry Hoffman, my first cousin by marriage. This was now a family battle, and I dug my heels in.

What we were up against became clear the day before our court appearance, when Dave Krathen and I met in Gary Farmer’s office in Fort Lauderdale and were dismayed to discover that Bush campaign attorneys had filed a half-dozen motions to stop our having the hearing before the specifics of our case became known. To my consternation, Bush’s people had hired the Greenberg Traurig law firm based in Miami, a formidable foe with hundreds of attorneys on staff. Incidentally, the firm’s founding partner and CEO was Larry Hoffman, my first cousin by marriage. This was now a family battle, and I dug my heels in.

First, we had to move our litigation forward while still keeping it from being transferred to another, and perhaps less accommodating, court. Second, because the Democratic Party had now jumped into the fray by demanding a manual recount in Palm Beach County, we had to be prepared to argue a range of issues well beyond the confusion stemming from the faulty ballot. More than anything else, we had to educate the public about what had taken place.

The challenges of doing so in such a short time frame were daunting, and our opposition had all the advantages. George W. Bush, brother of the governor of Florida, Jeb Bush, had technically already won the election, and Katherine Harris, the Secretary of State of the Commonwealth of Florida, was cochair of Bush’s Florida election committee. Harris had the power to declare that the mandatory recount already underway be stopped, a power she executed the following Monday morning in Palm Beach County, as she had already done in Broward, Miami-Dade, and Volusia Counties. At that moment more than ever, the public needed to be told not only what our legal team was doing but why.

By the afternoon of our November 14 appearance, the press was reporting allegations of electoral fraud throughout the state. Improper ballot design and defective equipment combined to create a flawed election, and a flawed election was what Palm Beach got. The effect was to make Palm Beach, where the first court hearing was to take place, ground zero in the post-election controversy.

The Nation Takes Notice, African Americans Protest Then and Earlier

It is difficult to describe the sea of people who descended upon what was otherwise a sleepy Florida courthouse, where attorneys, judges, and police all knew one another, and the only serious outside interference came from the hurricanes that blew in off the Atlantic. A hurricane had arrived that day too, but it wasn’t the kind that a meteorologist could have predicted.

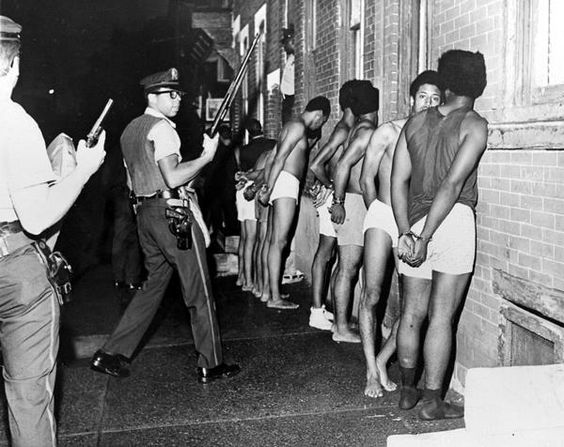

Thousands of protesters, mostly African Americans, angry because so many of their votes hadn’t been counted, had descended upon Palm Beach. The largest contingent of protesters, led by Reverend Jesse Jackson, marched in the streets and camped out in front of the courthouse, calling, as we did, for the vote recount to be resumed and for a full-fledged nonpartisan inquiry into the butterfly ballots. Standing in opposition to them were Confederate-flag wavers and self-proclaimed neo-Nazis. Claiming their places on the sidelines were hundreds of “volunteer” attorneys in Brooks Brothers suits, state police and sheriffs in riot gear, and television and press reporters from as far away as Los Angeles and Tokyo. Newscasters hovered overhead in helicopters, and their vans blocked the streets.

I felt a mix of emotions: a tremendous desire to remain steadfast in my commitment to represent my mother-in-law and so many more thousands of disenfranchised Florida voters, and trepidation that a race riot would overshadow what we sought to accomplish in court. Most of all, I felt a deep concern for our nation and its leadership.

Years earlier, amid race riots outside the Philadelphia courthouse, I had defended the Black Panthers on trumped-up murder and conspiracy charges. I had joined protest marches and demonstrations with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) while leading the court battle for higher wages, healthy working conditions, and gender equality on behalf of black janitorial trade unions and maids. Thanks to suits that I brought on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), we won the rights for young people to vote in the ward where they went to college if it differed from their home residences, and drafted inclusive new rules that were used to determine the selection of delegates for presidential conventions.

I don’t mention these things to beat my own drum or display my left-leaning liberal roots, but to put our greater national struggle into historical perspective. The sense of anger and betrayal that I felt in Palm Beach was made the more acute because I, a Jew from Brooklyn, and so many others of my generation—whites and blacks and Jews and Gentiles—had fought this battle before. Civil and voter rights legislation was our generation’s legacy. There I was, nearly forty-years later, fighting to reclaim lost ground.

I wouldn’t get to fire the opening salvo of that battle, however, if I couldn’t reach the courthouse. There were so many protesters, police, television crews, and attorneys that we had difficulty reaching the front steps. When our team finally arrived at the front doors, we found them locked by security guards fighting to keep the protest outside. Luckily, I saw a law clerk making his way toward a side entrance, and our team managed to slip in behind him.

I was dumbfounded by what came next. After our hearing was called to order, one judge after another recused her- or himself from hearing our case. No one, it seemed, wanted to jeopardize his career by trying such a high-profile and politically charged litigation—so much for our courageous justices.

Despondent, we left the courthouse fearing the worst. The only positive outcome was an opportunity to file new motions demanding that the election recount be resumed regardless of Katherine Harris’s orders. Our argument was simply that the recount from Palm Beach may demonstrate that Gore had actually won the election. If this proved to be the case, there would be no further need to seek the more difficult remedy of staging a new election.

The parade of judges recusing themselves continued the next day until, to our relief, Judge Jorge Labarga took the assignment. As we had anticipated, he deferred judgment on the issues regarding the ballot design, ostensibly because he was not certain the problem could be constitutionally remedied in state court. There was only one day a year set aside for a presidential election, and regardless of how confusing the choice of one ballot over another might be, ordering an election in Palm Beach, and not the entire nation, could be viewed as unconstitutional. That issue would not be decided that day. However, Labarga accepted our argument about the importance of permitting the manual recount to go forward.

WATCH: Sheller on CBS 3, Bush v. Gore Vote Recounts

Most importantly, Labarga directed the canvassing board to consider any marks on the punch card that clearly showed a voter’s intent. In other words, even a punch hole that had not completely removed the chad was deemed eligible to be counted. His order permitting the recount was the first judicial order in Florida of its kind and, needless to say, our Rogers and Kaplan case became national and then international news that night. I left the court feeling that we had accomplished a major step forward. I knew ahead of time that the decision would invariably be appealed and the butterfly ballot issues wouldn’t necessarily be decided in our favor, but we were well on the way toward establishing the legal framework that could be used to appeal the Florida vote in federal court and, in turn, the results of the 2000 election.

Frustratingly, twenty-seven days later, our case wasn’t the one that reached the US Supreme Court. While our Palm Beach litigation came first and was, I believe, the strongest case, the battle over the presidential election had spread into other, much larger counties throughout the state. Eventually, Al Gore’s team asked us to withdraw our complaint in favor of another.

Reluctantly Standing Down

My decision to stand down turned out to be the most regrettable of my entire career, for the stakes couldn’t have been higher. Knowing in hindsight what we do about the Bush presidency, I should not have left it in the hands of others to fight to uphold our nation’s civil rights—protections which I would soon see cast aside in favor of thinly veiled and self-serving corporate interests. I believe that Rogers and Kaplan would have been the strongest case to take before the Supreme Court, as it did not rest on politically complicated issues of federal versus states’ rights but on consumer fraud. The Palm Beach ballot was improperly designed and the Votomatic machines faulty. Easily proven facts and backed-up science, not ideology or rhetoric, would have ruled the day.

On November 17, three days after our hearing, I had a premonition about what was eventually to be decided by the high court. I took the last flight out of Palm Beach back to Philadelphia that day to attend the celebration of the 150th anniversary of my alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania Law School. The speaker for the festivities was US Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. I found her remarks genuine and inspiring. A tallish woman with white hair and wearing a light-colored dress, she spoke of the heroism and dedication of generations of woman who battled a patriarchal system for equality and how, in the years since then, women were entering law schools in ever-increasing numbers and making even greater contributions to the public good. As Justice O’Connor’s stirring speech ended, a fire alarm rang, and everyone in the law school auditorium went trooping out of the building with O’Connor aggressively pushing her way to the front of the line to be the first out the door.

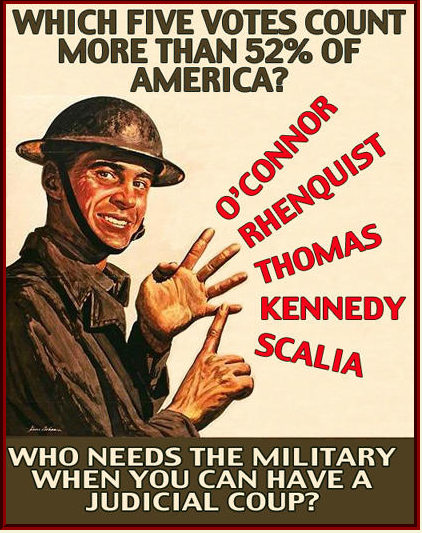

The alarm turned out to be false, but the shrill ringing in my ears continued when, on December 12, Justice O’Connor’s vote was the deciding one in the ruling that disenfranchised thousands of voters: men and women, young and old, blacks and whites, those who didn’t know enough to complain, and those who, like my mother-in-law, did. The court ruled that the state of Florida could not determine the meaning and application of its own laws since to do so would cause “irreparable harm” to petitioner George W. Bush. In other words, the Supreme Court violated the very principles of states’ rights that they had themselves set forth on numerous previous occasions. It was a stunning attack on states’ rights by a court that had hitherto held the expansion of states’ rights as its Holy Grail.

In addition to the victory of federal rights over states’ rights, the decision also presented an equally stunning refutation of what had, up until that point, been considered in state and federal courts to be a basic rule concerning conflict of interest: namely, that a judge may not sit on a case in which a family member is party, either as a litigant or an attorney. From that moment onward, judges apparently no longer needed recuse themselves in such cases. Justice Antonin Scalia participated in the Bush v. Gore case and voted in support of Bush even though his lawyer son worked with, and was supervised by, the attorney who represented Bush before the Supreme Court and whom President Bush would subsequently appoint as solicitor general. Scalia himself had been a recent guest at Bush’s ranch in Texas. Additionally, Justice Thomas’s wife, an attorney and congressional lobbyist, was so intimately involved in the Bush campaign that she was helping draw up a list of possible Bush appointees at more or less the same time her husband was adjudicating on whether Bush would become the next president.

Even Sandra Day O’Connor, on the eve of the election, displayed her bias when she publicly stated that a Gore victory would be a personal disaster. Her sentiments were echoed by her husband during an election-night party held before the votes had been tabulated, when it was believed that Gore and not Bush had won Florida and, hence, the presidency. He had said that Sandra would have to wait another four years before they could retire to Arizona or else a Democrat would get to appoint her replacement on the Supreme Court. A Democrat in our nation’s highest office simply wouldn’t do. Never mind the merits of the case Bush v. Gore, which she and the other justices were soon to hear.

When alarm bells rang at the University of Pennsylvania, I didn’t know that O’Connor would be the swing vote that would decide the election. My attention was still fixed on Palm Beach, on what could be done about the central problem as I saw it, how faulty machines and their ballots may have been used to favor one candidate over another. To that end, Gary Farmer and I joined another class action suit already underway, this time against the company that had manufactured the Votomatic machines. If we could prove that the machines were inferior and that those who put them into service in Florida knew it, we might find out what had actually happened in Palm Beach on Election Day. At the least, we could gain insight into the identities of the decision makers through discovery and depositions. Florida election officials could easily sidestep the media, but they couldn’t ignore a judge’s summons to testify under oath.

Rage Against the Machine

The class action suit we brought in January 2001 was filed in Illinois against Election Systems & Software (ES&S) and didn’t mention the disputed Bush v. Gore election. The principal allegation was that their Votomatic system was inherently faulty and produced incorrect counts. The machine and its results were the principal evidence in our favor. Subsidiaries and companies that licensed the machines, such as Data-Punch, were selling products and services necessary for the ongoing use of the Votomatic machines while failing to tell customers that the machines had serious defects that violated consumer fraud statutes. As the machines were used in 29% of the polling places in the 2000 election, we had abundant statistical information upon which to draw. Our team contributed what we had learned in Palm Beach, which could be used to compare and contrast the experience of the Votomatic’s usage elsewhere across the nation.

I don’t wish to burden you with ever finer details of how I believe a voter fraud was engineered in Florida, but as you will see in the chapters to come, the key to understanding the truth of a betrayal is often less a matter of legal reasoning than it is unraveling the tangled knot of the facts of a case. In Bush v. Gore, attention must be focused on what election officials knew about the Votomatic machines that were being used to tabulate the vote.

For those fortunate enough not to have cast a ballot by Votomatic, the machine essentially consists of a punch card with a plastic backing that should be replaced when it becomes stiff, although this is rarely the case. The voter slides the card into place over the ballot and uses a stylus to punch out a circle next to the names of the candidates he or she prefers. Theoretically, the punched-out chad lands into the T-strip below that contains chambers to hold the chads corresponding to where they had been on the punch card. There is no way for the voter to know whether or not the chad is in the tray. This is important because if the stylus hasn’t detached the chad, there is often no hole for the computer scanner to read when the cards are bundled and run through the counting machine. The vote is then not tabulated.

Our research revealed a variety of reasons why the chad is not removed, creating an “undervote,” which means the vote for the intended candidate isn’t counted. Made infamous by the Florida election, the hanging chad is a tiny fragment of paper that may literally be hanging by one or two edges. It may sometimes fall off into the tray, in which event the computer scanner counts the hole. Two other types of errant chads are ordinarily never counted. The “pregnant” chad occurs when a hole is poked in the ballot by the tip of the stylus, but remains in place. In the case of the dimpled chad, the stylus merely makes an indentation. Heavy punch card paper, stiff plastic backing, or imprecise positioning of the ballot all contribute to the undervote.

The cards and card stock, however, are not always to blame when the Votomatic fails. In 1968, for example, a flaw in the counting machine in Montana caused Richard Nixon to lose in Republican districts and his Democratic opponent, Hubert Humphrey, to fare poorly in areas where the Democrats were strong. Despite its many faults, which made it less reliable than any other voting method, there are nevertheless times and places where the Votomatic works just fine. Thus, the machine has well-known weaknesses that may or may not present themselves when used.

Although it seems clear that the Votomatic’s popularity had a great deal to do with ES&S’s legitimate lobbying efforts with officials in both parties, it is a temptation for dishonest politicians and their sponsors because of how easily it can be manipulated to produce false results. If someone, for example, were to use a Votomatic to commit a fraud, it would not be necessary to involve many people. The machine is susceptible to rigging both at the point of origin and at the polling place by using substandard ballot paper that produces chads, or doesn’t fit squarely into the Votomatic tray, or using machines that haven’t been properly maintained and serviced or have been purposefully misaligned.

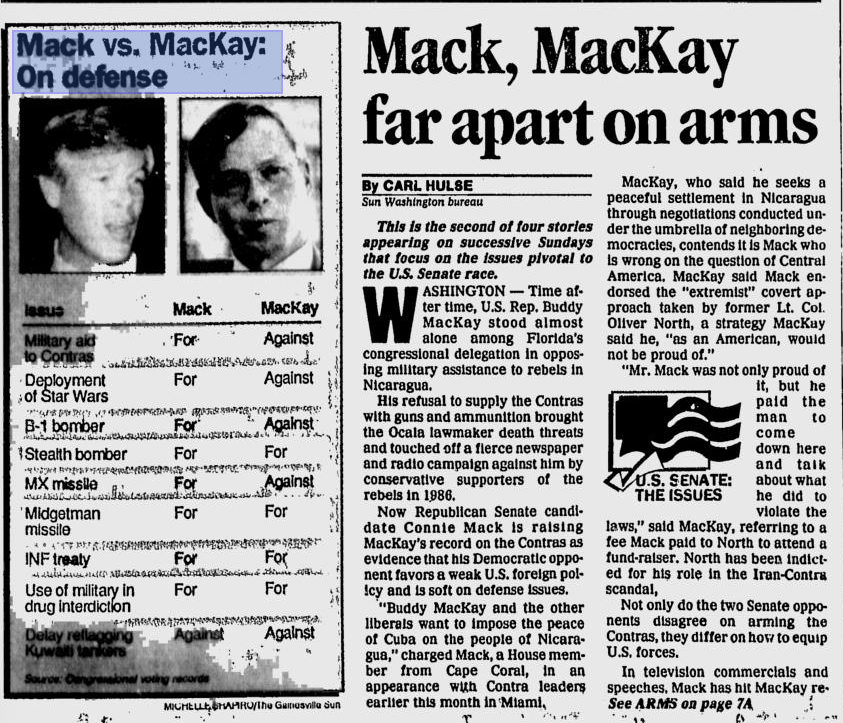

Our investigation revealed that this kind of tampering apparently took place in the 1988 election in Florida, in which suspicious results arose in many of the same counties in which fraud was suspected in the 2000 election. In the 1988 affair, Republican Connie Mack and Democrat Buddy Mackay competed for a seat in the U.S. Senate, with Mack defeating Mackay by 34,518 votes out of more than four million cast. In four strong Democratic counties, the Votomatic system recorded 233,000 more votes in the presidential contest than in the senatorial race. If the Votomatic results were to be believed, this would mean that more people in these counties voted for state treasurer and secretary of state than for U.S. senator.

Oddly enough, even the most thorough analysis of Bush v. Gore made no mention of Mackay v. Mack. The analysis undertaken by Knight-Ridder newspapers and U.S.A. Today came to the conclusion that Bush won but, on the other hand, Gore had also won. As the report explained, by applying the strictest and most frequently used means of counting, Bush ended up with a lead of 152 votes rather than the official 407. However, if votes that previously hadn’t been were counted, voter intent dictated that Gore won by approximately 15,000 votes.

The study laid much blame on the butterfly ballot in Palm Beach County, where Votomatic-type machines were used. Not only had my mother-in-law and I complained about it, but the newspaper researchers did as well. According to them, the alignment of names and punch holes on the cards made it difficult for many voters to figure out how to cast their ballot for Gore and, consequently, they ended up voting for Buchanan or for both of them, creating an overvote in which the machine saw multiple holes for the same office and rejected it. According to the newspaper articles, the election altogether produced 111,000 overvotes. Gore was coupled with another candidate in the overvotes, though not necessarily Buchanan, 76% of the time. The high number of Gore couplings indicated that he was the voter’s choice in the large majority of, if not all, such instances.

However, the overvotes were not confined to the Votomatic districts. In Duval County, which is predominantly black and Democratic, a dot mysteriously showed up on computer scanning machines, causing the counting device to see it as a vote. When the dot was coupled with a vote for another candidate, which was almost always Gore, the machine saw two votes and counted neither, leading to a loss of about 3,000 votes for Gore. Over or under counting also took place in districts that used ballots in which the voter filled in the oblong area next to the chosen candidate with a provided pencil but, in these instances, the voter’s intent was usually clear.

A further reason to believe that most of the uncounted overvotes had been Gore’s, said the study, is that Gore ran 25,000 votes behind the Democratic candidate for senator in the overvote count. In other words, this was the opposite of the Mackay loss, in which he ran astoundingly behind the Democratic candidate for president. To the authors of the Knight-Ridder and U.S.A. Today study, the discrepancy in the senatorial and presidential votes indicated that chances were good that most people who voted for the Democrat for senator also intended to vote for the Democrat for president. This generalization has merit, but it was not the only or most significant inference to draw. In order for there to be no chicanery in the election, we must believe that the Democratic voters who were too confused to figure out how to vote for president were somehow bright enough to figure out how to vote for U.S. senator, a point which has been ignored in everything I’ve read on the subject.

It is further apparent that Gore was not only hurt by overvotes, but also by undervotes. This could have happened by providing targeted districts with imperceptibly thicker or more resilient punch card paper, making it more difficult for a stylus to fully penetrate from the top to bottom. Alternately, the paper could have been cut in such a way as to be slightly misaligned at the Gore slot, preventing a chad or partial chad to be released. Regardless of the paper used in the ballot, however, the percentage of overvotes and undervotes was astounding even by Votomatic standards.

I don’t pretend to know exactly what happened in Florida, but based on election law expert Gregory Harvey’s studies and the Knight-Ridder/U.S.A statistical analysis, which has never been refuted, I can see no way in which the results could have come about by chance. Citizens were stripped of their most fundamental right to vote. Worse, their vote would be counted with the evident winners, the Republican Party. With George W. Bush as president, and Jeb Bush, the governor of Florida, W.’s chances for reelection would be significantly enhanced with his party and his older brother in power.

The best place to find the truth about what happened is with Election Systems and Software (ES&S), which was why Gary Farmer and I joined the litigation team bringing the class action suit against them. But as soon as we took up the case, it had to be dropped. The plaintiffs no longer faced being cheated by the suspect Votomatics because the machines were withdrawn before we could litigate the case in court. After the chads went flying in Florida, election officials across the county would no longer touch a Votomatic with a ten-foot stylus. Had the suit actually been litigated, the plaintiff attorneys, including Gary and I, could have questioned ES&S officials about their deal-making with Florida politicians and might have also been able to take depositions from the civil-service and other Floridians who put the Votomatics into service.

We may have to wait years for new evidence to be unearthed by a historian about what happened in Palm Beach in 2000. But as Gary and I have already found by submitting several of the preserved punch cards from Democratic districts to experts, we know that the paper stock, which was not uniform throughout the state, created both over-and under-counting. Were poor quality punch cards sent to polling stations where Gore was expected to do well and higher-quality punch cards sent elsewhere?

I would also call your attention to the immediate aftermath of the 2000 election. To get to its importance, assume, for the moment, that the presidential election in Florida was entirely free of malfeasance on the part of election officials. In that event, Floridian officials would logically be upset at the company whose equipment failures caused the state to suffer national and international embarrassment as they tried to explain how such gross failures could occur on their watch. Significantly, this was not the case, something that should give all voters cause for serious concern.

Floridian officials under Jeb Bush not only failed to launch a proper investigation, but they also bought more ES&S machines. Thanks to lobbyist Sandra Mortham, the former Florida secretary of state, twelve Florida counties bought these new voting machines for a total of $70.6 million dollars in taxpayers’ money. The newly purchased ES&S machines arrived loaded with problems, including the mysterious dot that had turned up on some machines in Gore districts in the 2000 election. In the 2002 Democratic primary to choose who would oppose incumbent Jeb Bush for governor, front-runner Janet Reno received an undervote of about 48 percent in heavily Democratic Miami-Dade County. She demanded a recount that was ultimately averted when the election officials inexplicably managed to reconstruct some of the missing votes out of the computer’s innards. Reno, not wishing to protract the contest into November, conceded—although like Gore, she had probably won—leaving it up to her lesser-known opponent to unseat Jeb Bush.

He didn’t.

The rest, as they say, is history. As a result of the “stolen” 2000 election, I believe our nation was led into two needless wars instead of one warranted police action. Hundreds of thousands of innocents died and torture was legally sanctioned. Our nation became conquerors and invaders, not the liberators of Eisenhower’s and MacArthur’s times. And in the process, the rich got richer, and the tables tilted further in favor of banks, financiers, and the military industrial complex. Fewer than four hundred families today now possess as many assets as the bottom 150 million, and 95 percent of our nation’s economic gains go to the richest 1 percent of Americans., As the average worker is struggling to make ends meet on minimum wage, the owners of our largest corporations are experiencing record-breaking profits, with the CEOs’ salaries, stock options, and other benefits five hundred times higher than their average employee.

Had Bush not taken office, we may not have been saddled with draconian Voter ID and redistricting laws that have disenfranchised hundreds of thousands of voters. We also may not have been sold a false bill of goods about the so-called “paper trail” we can use to verify election results—the one in which voters are excluded from actually examining the ballots and where county auditors are not permitted to inspect the proprietary computer software that is used to tabulate the votes.

Under a different chief executive, we might not have a judiciary that increasingly operates on a two-tier system of justice—one for the well off and one for the poor. As has become a veritable cliché in our nation’s courts, a defendant with a public defender goes to prison and a defendant with private counsel walks. Most unfair of all, criminals who run companies that steal hundreds of millions of dollars or are responsible for killing or injuring hundreds of thousands of people receive bonuses and promotions, and the thief in the supermarket or the street-corner mugger goes to jail.

With a different chief executive, we may not have had a Supreme Court that decided in favor of Citizen’s United, in which corporations have been granted corporate personhood with constitutional rights similar to yours and mine, including that of free speech. That a corporation is not a flesh-and-blood person, can live indefinitely, be bought and sold, headquartered in a foreign country, can amass immense wealth that is not subject to the same taxes as you and me, and whose owners cannot be legally liable for wrongs it commits is beside the point—or so the Supreme Court would have us believe.

This same court applied similarly twisted logic when striking down federal campaign contribution regulations (for the first time in history) by increasing the amount of money donors can contribute to political campaigns. As money constitutes free speech, so our judiciary tells us, why shouldn’t corporations be permitted to give freely? Never mind that a dairyman on small, family-run New Hampshire farm can’t compete with the billions that the Monsanto corporation has to spend.

The Dawn of the Pharmaceutical-Industrial Complex of the Modern Age

I’ll not argue that some or all of these things wouldn’t have occurred had Gore, not Bush, sat in the Oval Office, or that Democrats aren’t also responsible for many of our nation’s travails. But I can tell you with absolute certainty that the 2000 election brought forth a massive tidal wave of corporate influence that infected our government at all levels. Corporate titans, today’s equivalent of yesterday’s robber barons, were permitted to buy elections, purchase state legislatures, appoint judges, and write laws to benefit themselves. Nowhere is this more evident than with the pharmaceutical industry chieftains, whose lobbyists became key players in the Bush administration, and under whose influence the FDA became the “fast drug approval” agency.

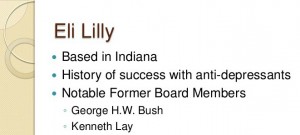

Among the most powerful of those pharmaceutical corporations is Eli Lilly, whom Gary Farmer and I would take to court in the same state where we had earlier filed voter fraud charges, and which was the case that became the genesis of the litigation described in these pages. In retrospect, our choice to team-up and take on Lilly was providential—either that or a recipe for disaster. Not only were members of the Bush family major stockholders in Eli Lily and other pharmaceutical companies, but they were beholden to the industry in other ways as well.

After leaving his post as CIA director, George H. W. Bush was appointed a director on the Lilly board, an honor bestowed upon him by the wealthy and influential father of future Vice-President Dan Quayle, the owner of a controlling interest in the company. Then, and later, George H.W. Bush would successfully lobby to permit drug companies to sell obsolete or domestically-banned pharmaceuticals to Third World countries. While Vice-President, he would continue to act on behalf of pharmaceutical company interests by personally requesting the IRS to give special tax breaks for Lilly and other drug companies.

Also serving on Lilly’s board of directors was Bush 2000 campaign contributor Ken Lay, the former CEO of Enron, whom the President George W. Bush and the First Lady joined on an Enron corporate jet on their first trip to Washington after winning the election. All of us know, of course, what happened there: Enron would go on to become the poster-child of institutionalized, systematic and creatively planned accounting fraud, that which would set the stage for the Wall Street subprime mortgage crisis of 2008.

As would soon become evident to Gary and me, the Bush connection to Eli Lilly and the Big Pharma “alumni club” ran much deeper than just this. Mitch Daniels, a former vice president of Lilly, became Bush’s director of management and budget. Sidney Taurel, another former Lilly CEO, would join Bush’s Homeland Security Advisory Council. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld served on the board of Eli Lilly partners Amylin Pharmaceuticals and Gilead Sciences. Similarly, administration veterans would transition easily back and forth to Lilly’s senior management. Among them was Alex Azar, who was Bush’s deputy secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, during which he oversaw such agencies as the FDA, the National Institute of Health (NIH), the Center for Disease Control (CDC), and the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services. After leaving the Bush administration, Azar would become the senior vice president of corporate affairs and communication for Lilly.

As would soon become evident to Gary and me, the Bush connection to Eli Lilly and the Big Pharma “alumni club” ran much deeper than just this. Mitch Daniels, a former vice president of Lilly, became Bush’s director of management and budget. Sidney Taurel, another former Lilly CEO, would join Bush’s Homeland Security Advisory Council. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld served on the board of Eli Lilly partners Amylin Pharmaceuticals and Gilead Sciences. Similarly, administration veterans would transition easily back and forth to Lilly’s senior management. Among them was Alex Azar, who was Bush’s deputy secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, during which he oversaw such agencies as the FDA, the National Institute of Health (NIH), the Center for Disease Control (CDC), and the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services. After leaving the Bush administration, Azar would become the senior vice president of corporate affairs and communication for Lilly.

Then there was Big Pharma’s shill Dr. Andrew von Eschenback, whom President Bush appointed the head of the National Cancer Institute and who would later be tapped to head the FDA. As the Union of Concerned Scientists and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Institute of Medicine would report in 2006, under Eschenback’s tenure, the agency was “perverting science for political and financial benefactors.”

Care to guess which drug company dominated the lobbying pack? In our new pharmaceutical litigation, Gary and I encountered so many conflicts of interest that our case should have been justifiably called Lillygate.

Read more of the book, available on Amazon or by request at your local bookstore.

Contact us: news@nationbetrayed.com.

Pharmageddon: A Nation Betrayed is published under the Cape Cedar Media imprint. For more information, contact news@nationbetrayed.